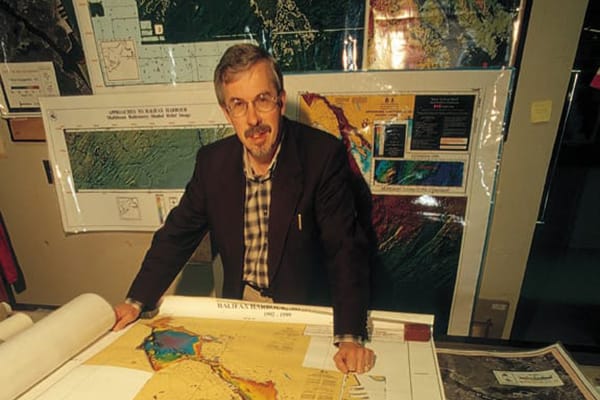

Gordon Fader knows the bottom of Halifax Harbour the way most people know their own neighbourhoods. For the Halifax marine geologist, every shipwreck, every rock outcropping, every spot where the sediment is slightly deeper tells a dramatic story. The bones of past tragedy litter the harbour floor, spinning tales of heroism, folly and sudden death.

In a painstaking underwater survey that has taken a decade to complete, Fader and his colleagues have mapped the entire harbour with sidescan sonar and made hundreds of passes with small, unmanned submarines known as ROVs (remotely operated vehicles). Often, they've looked Halifax's most dramatic historical events squarely in the face.

In 1746, three years before the city was founded, a huge French armada under the command of Duc d'Anville sailed into Bedford Basin. D'Anville's intention was to reclaim Louisbourg and Annapolis Royal for the French crown, then ransack Boston. But on the long journey across the Atlantic, epidemic had decimated the crew and scuttled the plan, forcing him to abandon most of his ships to rot in the Basin. Fader and his colleagues have found the remains of that great fleet just off the Fairview container pier.

The pieces of hundreds of other stories also decorate Fader's new charts. On The Narrows seabed a railway track, part of the first harbour bridge that inexplicably collapsed one night a century ago, still winds its way from Halifax to Dartmouth. The wreck of the HMS Tribune lies below the Herring Cove cliff where she was dashed to bits in 1797, taking 250 lives with her. Dozens of wrecks, debris, even a line of 22 perfectly preserved Volvo automobiles, all have stories to tell. Fader has seen them all from the comfort of his own office at the Bedford Institute of Oceanography (BIO), revealed through sidescan sonar, a technology that visually strips the water away and shows the landscape below in dramatic, three dimensional detail.

The images that evoke the most emotion are those that relate to the events of December 6, 1917. Most Atlantic Canadians know the story. Two ships, the Mont Blanc and the Imo, collided in what would have been simply a mid-harbour fender bender-except that the Mont Blanc happened to be packed to the gunnels with explosives bound for the Western Front. The resulting sparks ignited the incendiaries piled on deck. At 9:04:35 a.m. the newly installed seismograph at Dalhousie College recorded a huge blast as the Mont Blanc and most of north end Halifax disappeared in a flash of white light and a mile high cloud more like a piece of cauliflower than a mushroom.

Just over his left shoulder, Fader's office window affords a view of Halifax Harbour and the spot where the Mont Blanc ignited. Had this office existed in 1917, it might not be here now.

Fader might not be either, if his father had lived a few streets closer to the harbour. Gordon Fader Sr. was a baby, lying in his crib in his Clifton Street home on that December morning. As the shockwave from the blast funnelled between Fort Needham Hill and Citadel Hill, it blew out the child's bedroom windows. Had he been a little older, the senior Fader might have been sitting up and been blinded by the glass, as hundreds of others were that day. As it was, a shard of falling glass left an ugly gash in his neck and a prominent scar that would remain for the rest of his life.

He was lucky.

Like a collector looking for a favourite baseball card, Fader thumbs through a thick stack of sidescan sonar images. The images are surreal, with computer enhanced colours adding to the effect. In one, the smooth, steep banks of Georges Island continue down below the surface to the harbour floor, with a well-preserved shipwreck clinging to the sloping side like a bug. Another reveals an undulating harbour bottom with the neat outline of a sunken ship tucked into the ridges. Fader knows the names of most of the vessels.

He's still looking for the Mont Blanc. The popular wisdom is that the central player in the Halifax Explosion was blown into tiny chunks that rained down on the city. Indeed, a large piece of the anchor did land in Armdale and another piece in Albro Lake. But Fader doesn't believe the entire ship disintegrated. Somewhere in the murky depths of the harbour, he believes a large piece of the Mont Blanc still exists-maybe the ship's huge boilers, hauled into deep water by dredging operations. Every time new reports of shipwrecks surface, his heart races. Early in 2001, a navy sonagraph identified a new wreck in The Narrows, and recently a sport diver spotted what looked like a "bowlike structure" poking out of the bottom. Both sightings have yet to be positively identified.

Fader and his BIO colleagues have found one key to the puzzle, however: ground zero. He says the popular misconception remains that the Mont Blanc exploded in the middle of the harbour, but that's just not so. He says she was actually aground on the Halifax shoreline, her bow wedged into the mud beside Pier 6.

Pier 6 was obliterated by the blast, but a sidescan sonar survey has located its remains-a series of 10 pilings just north of the current Novadock. But it's what is not there that's particularly significant-the massive crater that most people always believed to exist. Fader has studied craters made by hydrogen bomb tests in the Pacific and says the Halifax Explosion crater was probably less than three metres deep to begin with and has probably been destroyed by dredging and infilling. Or, it may have been filled by the remains of the Mont Blanc.

A naval officer holding a chart knocks at Fader's open office door. The navy is planning underwater maneuvers off Chebucto Head and needs to know quickly if there are any wrecks or debris in the area that will snag their towed sonar equipment. Fader stares at the unrolled chart and points out several wrecks to the young officer, who takes notes. "This could take a while. Could you come back in a half hour," Fader finally asks the officer.

The officer agrees and Fader returns to his story.

One of the problems, he says, is that the remains of the Mont Blanc may have been hauled out to deeper water during the clean-up operations without a lot of fanfare. In the wake of the disaster, most artifacts that would have had historical significance today were destroyed or buried. "There was never any thought at the time of preserving them for their historical value. The people of Halifax weren't in the mood to keep any souvenirs of the explosion. It would have been considered extremely bad taste. They certainly didn't want to have to look at what was left of the Mont Blanc every day."

Fader admits that the hunt for explosion artifacts is far from over. His 10-year survey has identified thousands of individual targets on the harbour floor-artifacts that remain well preserved because of the nature of the rocky sea bottom. Now each one of them must be painstakingly examined by an ROV or a scuba diver. "This study is just getting started," he says. "We've found 52 new magnetic anomalies at the mouth of the harbour that we believe to be wrecks that we haven't identified yet. The Narrows is a gold mine for artifacts. There's enough there to keep a team of archaeologists busy for a very long time.