Debbie Brady creates stunning, unique art

Happenstance led late-in-life photographer Debbie Brady to uncover the abstract beauty of oyster shells.

The lifetime lover of the coast gathered a collection of found beach treasures one day in 2016 and brought them back inland to the apple farm in rural Prince Edward Island where she lives with her husband.

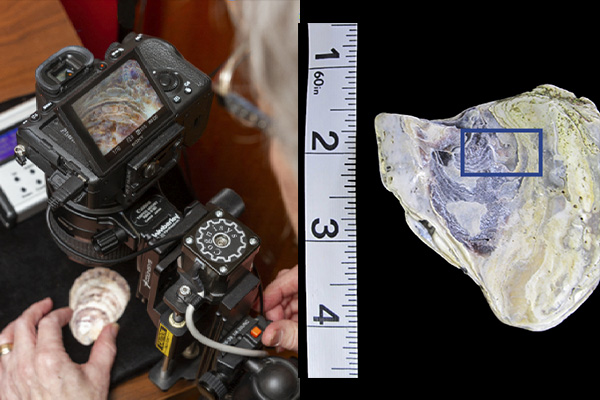

She put a weathered oyster shell under her macro camera lens, a specialized attachment that shoots extreme close-ups. The magnified images she captured captivated her.

“It gave me goosebumps to see the lines, unexpected shadows and shades of colour hidden from the naked eye,” she recalls. “I was seeing something extraordinarily new in something so familiar and I wanted to share my discovery with everyone.”

Others weren’t so taken by the otherworldly images. “When I first started doing it, nobody really cared,” Brady says. “Abstracts can be a challenge

for people.”

While people thought the pictures were beautiful, they didn’t resonate until she explained their genesis. “Artists do paintings where they pour them and swirl them and those are very pretty and difficult to do,” she says. “But oyster art is of a subject that people know.”

At her gallery next to her studio at the apple farm in Tyne Valley (part of the “Canadian Oyster Coast,” in another bit of happenstance), visitors can hold a camera, look down at a shell and see nature’s hidden beauty for themselves.

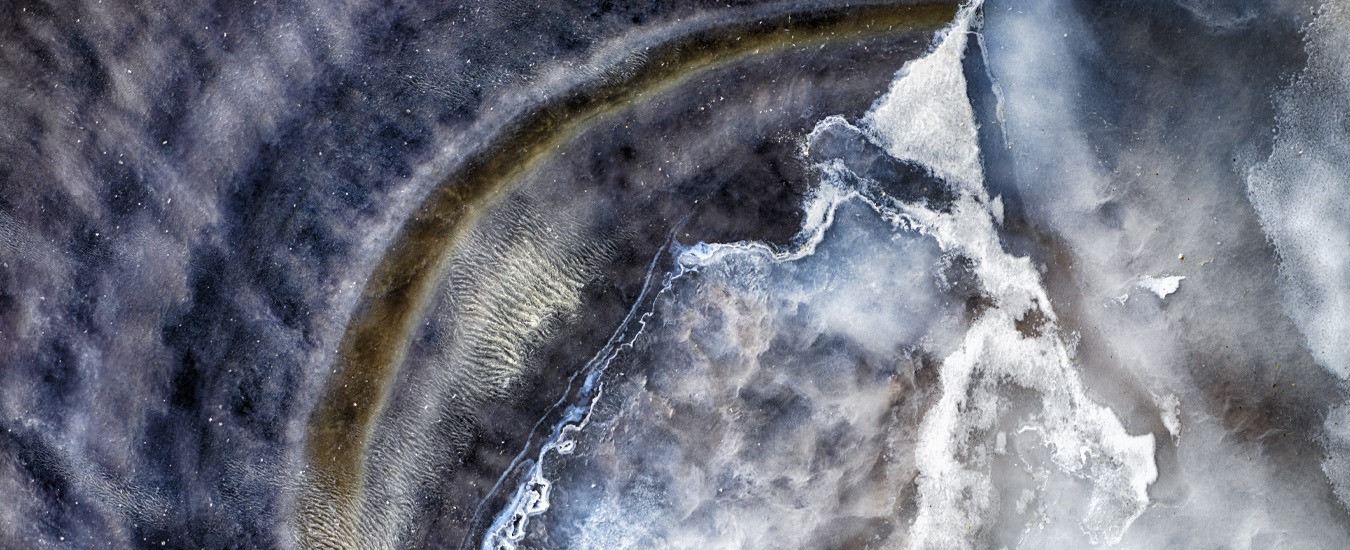

With her macro lens, Brady magnifies a tiny portion of an oyster shell, creating works that sometimes resemble a faraway galaxy. Photos courtesy of Debbie Brady

But Brady’s creations are no simple point and shoot. The now-accredited fine arts photographer spent a few years collecting shells, cataloguing and perfecting her technique before launching “Oyster Art,” a niche collection of photographic abstracts on stretched canvas, acrylic and fine art prints.

Brady turns off the heat pump in her studio to make things as still as possible. Her camera is on a tripod. (A handheld would generate too much movement for the close-ups that fixate on a tiny part of a shell.) She might take as many as 80 photos, shifting the point of focus over one small section in miniscule increments. She enlarges the images on her computer screen and sifts through to weed out blurry ones.

The in-focus pictures are stacked and blended to create a single image with swirls of colour and intricate patterns.

Brady says the process is tedious, involving a lot of math and calculations. But she’s always been driven by details and curiosity, even as a nursing student at Dalhousie University before she moved to PEI and raised four sons.

She dabbled in art, including soft sculpture as her kids were growing up. As they left home, she went back to school to study graphic design and opened her own business. She had a little point-and-shoot camera for years, but it wasn’t until 2009 that she bought her first DSLR, a digital camera that allows interchangeable lenses.

“Back then, there wasn’t access to all the online instruction now available,” she says. “It sat in the box for a while before I attempted taking photos simply using the auto setting.” Her love of detail and her “advanced degree in curiosity” led her to buy her first macro lens in 2012. She took some photography classes and, she says, “inevitably gravitated to the tiniest things.”

Brady tried feathers and a pussy willow as it went to seed before stumbling upon oyster shells. She’s allergic to the mollusks, but her “happy place” is walking along the shore. It’s a pastime she’s enjoyed since summer visits as a child with her father’s family on Cape Sable Island, on the southernmost tip of Nova Scotia.

With magnification five times larger than real life, her current macro lens shows mussels are nothing special, while lobster shells are “just a bunch of dots,” says Brady. “I could do something graphic that I would love, but not macro.”

Oysters reveal the wonders of fractals. Brady learned about the concept of complex patterns that are repeated again and again at different scales in nature and art from a visitor at an exhibit she hosted.

Not every oyster is photogenic. Brady estimates that only about five to 10 per cent of PEI varieties are worthy of art. She’s found oysters from Denmark, an entirely different species, are closer to 90 per cent photogenic.

“Weathered oyster shells have much more in them that I can capture,” she says. “It’s a whole world I had no idea I was going to get involved in that’s been just such a treat for me.”